Food provides the energy, nutrients, and building blocks the body requires to survive. When you stop eating, the body begins to adapt immediately. These adaptations occur in stages and affect multiple systems, including metabolism, the immune system, organs, hormones, and mental function. Studying these changes highlights both the human body’s resilience and its limits under prolonged nutrient deprivation.

Immediate Energy Use

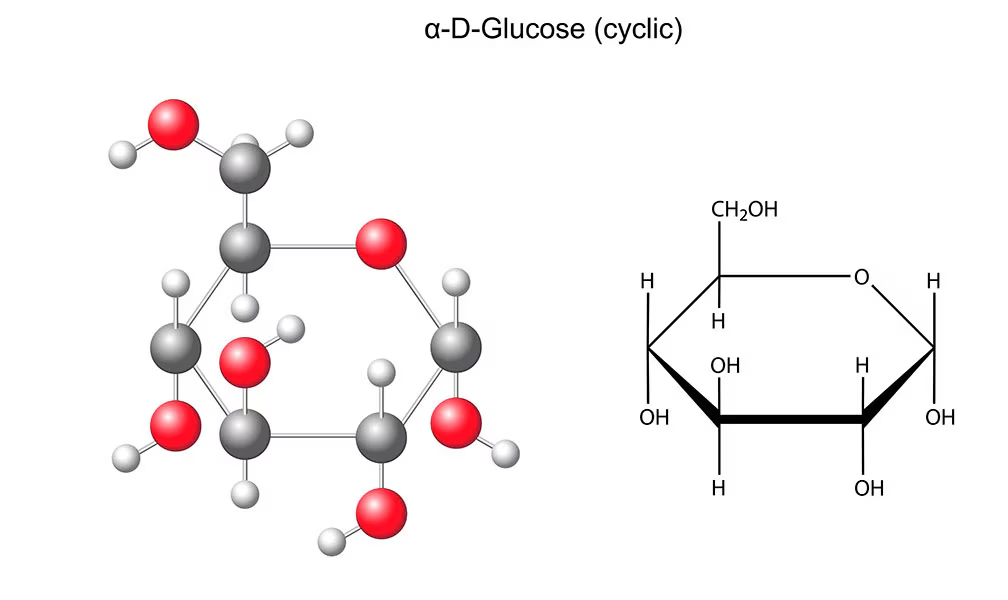

The body relies on glucose from the blood as its primary energy source. Within hours of missing a meal, blood sugar levels decline. You may feel lightheaded, weak, or irritable. To compensate, the liver releases stored glycogen into the bloodstream. Muscles also contribute glycogen, breaking it down into glucose for energy. This stage, which lasts roughly 12 to 24 hours depending on prior nutrition and activity, maintains energy temporarily but cannot continue indefinitely.

Fat Metabolism and the Onset of Ketosis

Once glycogen stores are depleted, the body turns to fat for fuel. Fat cells release fatty acids, which the liver converts into ketone bodies. Ketones serve as an alternative energy source, especially for the brain, which cannot use fatty acids directly. Ketosis typically begins within 2 to 3 days without food. Early signs include fatigue, mild headaches, irritability, and a distinct fruity odor on the breath due to ketones. Ketosis demonstrates the body’s ability to adapt, but it also stresses organs and signals energy scarcity.

Protein Breakdown and Muscle Wasting

Prolonged food deprivation forces the body to use protein as an energy source. Muscle tissue, including skeletal muscle, begins to break down to provide amino acids for critical functions. The body prioritizes vital organs, such as the heart, liver, and kidneys, while skeletal muscles shrink. Individuals often experience profound weakness, reduced endurance, and slower recovery from minor injuries. Over weeks, this stage leads to severe muscle atrophy, affecting both mobility and overall health.

Immune System Decline

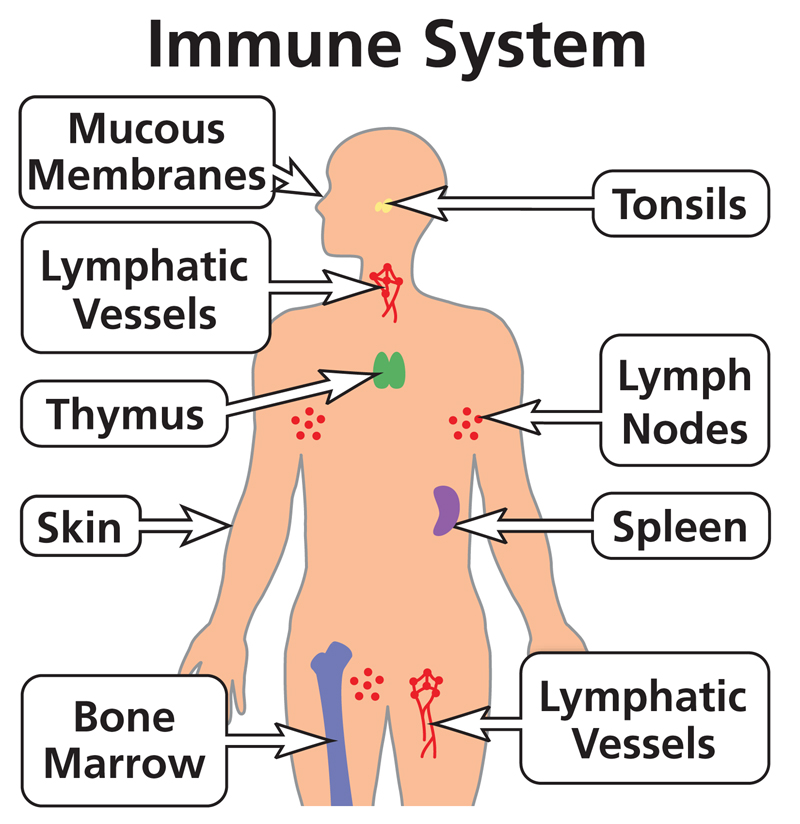

The immune system suffers quickly during starvation. White blood cell production drops, reducing the body’s ability to fight infections. Antibody production decreases because the body lacks sufficient protein. Skin, hair, and nails show visible signs of nutrient deficiency. Minor injuries heal slowly, and infections become more severe. Chronic starvation dramatically increases vulnerability to illnesses like pneumonia, influenza, and gastrointestinal infections. In historical famines, secondary infections caused the majority of deaths among malnourished populations.

Hormonal and Metabolic Adjustments

The endocrine system reacts strongly to a lack of nutrients. Insulin secretion drops, slowing glucose uptake and conserving energy. Thyroid hormone levels decline, reducing overall metabolism. Reproductive hormones decrease significantly. Women may stop menstruating, and fertility declines. Men experience lowered testosterone, reducing muscle mass and libido. The heart rate slows to conserve energy, but this adaptation can increase the risk of arrhythmias and, in extreme cases, heart failure. These hormonal shifts demonstrate how starvation prioritizes survival over reproduction and growth.

Digestive System Changes

The digestive system also adapts during prolonged food scarcity. The stomach and intestines shrink slightly due to reduced activity. Digestive enzyme production drops, making the body less efficient at breaking down food once it returns. Constipation, bloating, and abdominal discomfort are common. Over time, gut microbiota shifts, which can further affect nutrient absorption and overall health. Reintroducing food must be gradual; otherwise, the digestive system can become overwhelmed, leading to serious complications.

Mental and Cognitive Impacts

The brain requires a constant supply of energy to function properly. Without adequate food, cognitive abilities decline. Concentration, memory, and decision-making deteriorate. Mood swings, irritability, anxiety, and depression are common. Prolonged starvation can trigger severe psychological effects, including hallucinations, paranoia, and apathy. Studies of famine survivors show that mental fatigue often appears before visible physical deterioration, highlighting the brain’s sensitivity to energy scarcity.

Long-Term Adaptations to Starvation

If food deprivation continues for weeks, the body enters a survival mode. Metabolism slows drastically, reducing energy expenditure. Physical activity becomes minimal, and the body prioritizes maintaining core functions such as breathing and circulation. Growth and reproductive capacity are sacrificed. Over time, vital organs deteriorate. Liver function declines, kidneys face increased strain, and the heart weakens. Eventually, prolonged starvation without intervention leads to multi-organ failure and death.

Historical and Clinical Examples

Historical famines provide concrete evidence of the body’s response to starvation. During the Great Irish Famine in the 19th century, survivors experienced extreme muscle wasting, immune suppression, and cognitive decline. Clinical studies of individuals in concentration camps during World War II show similar patterns, with organ failure often following prolonged malnutrition. Modern medical research confirms these findings: patients subjected to weeks of food deprivation develop electrolyte imbalances, cardiac complications, and severe mental fatigue. These examples illustrate both the body’s ability to adapt and its vulnerability under extreme stress.

Refeeding and Recovery

Reintroducing food after prolonged starvation requires careful planning. Sudden refeeding can trigger electrolyte imbalances, heart failure, or refeeding syndrome. Gradual feeding allows the body to adjust, replenishing glycogen, restoring protein stores, and repairing damaged tissue. Small, frequent meals are ideal for safely restoring energy levels. Hormonal and metabolic systems also recover slowly. Full recovery can take weeks to months, depending on the duration of starvation and prior nutritional status.

Conclusion

Starvation triggers a complex series of physiological responses. The body initially uses glucose, then fat, and eventually protein to survive. Immune function, cognitive ability, and organ health decline over time. Hormonal shifts slow metabolism and reduce reproductive capability. Digestive and cardiovascular systems adjust to conserve energy. Awareness of these processes emphasizes the importance of consistent nutrition. Studying starvation provides insight into human resilience and the critical limits of survival. It reveals both the body’s remarkable ability to adapt and the severe consequences of prolonged nutrient deprivation.

Add comment