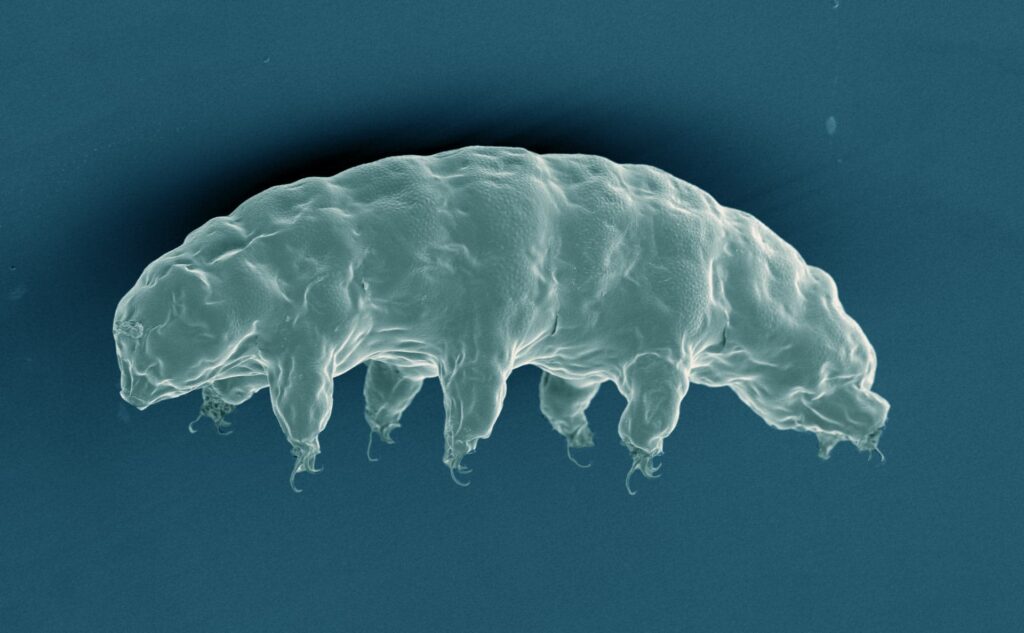

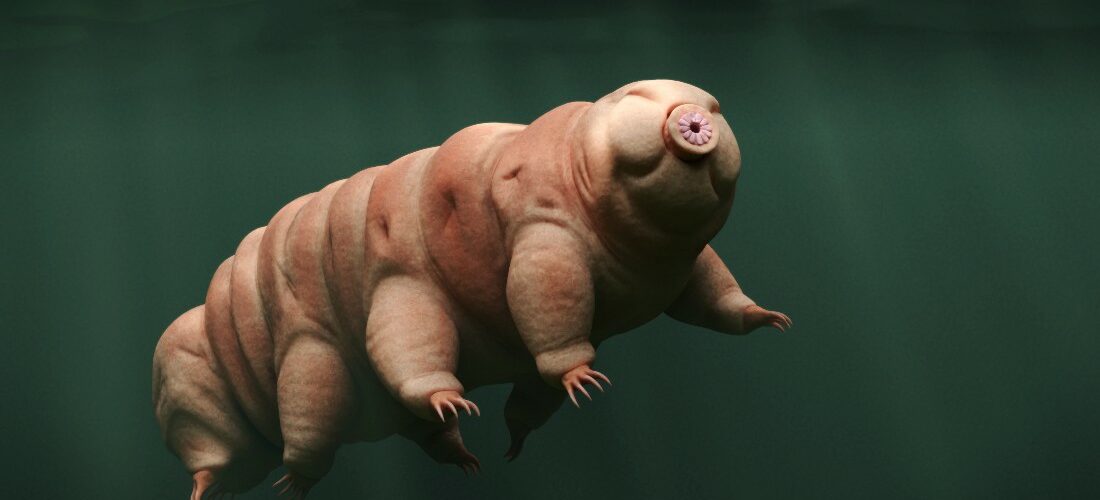

Tardigrades, also called water bears, are microscopic creatures famous for surviving extreme environments that would kill almost any other organism. Measuring less than a millimeter, they inhabit moss, lichen, soil, freshwater, and even deep oceans and polar ice. Despite their small size, they have complex anatomy, including segmented bodies, eight legs, and clawed appendages. Their adaptability makes them a focus of research in biology, medicine, and astrobiology.

These creatures inspire curiosity and study because of their extraordinary resilience. Observing tardigrades under a microscope shows slow, deliberate movements, feeding behavior, and survival strategies in real time. Their ability to withstand extreme heat, freezing, radiation, and the vacuum of space raises questions about the limits of life and the cellular mechanisms behind survival.

Physical Structure and Anatomy

Tardigrades have a head segment and four body segments, each with a pair of legs ending in claws or adhesive pads that allow movement across surfaces. Their external cuticle provides protection and is periodically molted to accommodate growth. Internally, tardigrades possess a complete digestive system, including a mouth, pharynx, and intestine, allowing them to feed on plant cells, algae, and microorganisms. Some species pierce cells to extract nutrients.

Their nervous system includes a brain and longitudinal nerve cords that control movement and sensory perception. This combination of simple external structure with specialized internal organs allows them to survive in a wide range of environments. Reproduction varies: some species reproduce sexually, while others use parthenogenesis, and their eggs are often as resilient as adults.

Studying their anatomy provides insight into survival strategies at the microscopic level. Students observing these creatures learn how specialized adaptations enable persistence in extreme conditions and the ways small-scale biological features influence overall survival.

Cryptobiosis: Survival in Extreme Conditions

Tardigrades survive extreme stress through cryptobiosis, a state in which metabolism nearly stops. In this form, they retract their legs and curl into a tun, losing almost all water and reducing metabolic activity to undetectable levels. Protective proteins stabilize cellular structures, and sugars like trehalose replace water to prevent damage, allowing cells to maintain integrity for years.

This adaptation enables survival under dehydration, extreme heat, freezing, high radiation, and even the vacuum of space. Scientists study cryptobiosis to understand DNA protection, cellular repair, and long-term survival strategies. Students observing this phenomenon see firsthand how biological systems pause life processes to endure harsh conditions.

Cryptobiosis also connects molecular biology, ecology, and evolution. By understanding these mechanisms, researchers develop insights into biotechnologies, such as preserving cells, tissues, and even organs under stress, highlighting the practical applications of studying extreme life forms.

Temperature and Radiation Resistance

Tardigrades endure temperatures ranging from near absolute zero to over 150°C. Their cells produce protective proteins and antioxidants to prevent heat and cold damage, while the tun state provides additional protection. They can repair cellular damage once conditions normalize, showing remarkable resilience and adaptability.

These creatures also resist high levels of radiation. DNA repair proteins and protective molecules allow survival even under gamma-ray and UV exposure, conditions fatal to most life forms. This ability challenges assumptions about environmental limits and provides insights for medicine and astrobiology.

Habitat and Distribution

Tardigrades are found on every continent, including Antarctica, inhabiting mosses, lichens, soil, freshwater, and marine sediments. Some species thrive in extreme environments like hot springs, deep ocean trenches, and polar ice, demonstrating their versatility and evolutionary success.

Distribution depends on moisture, temperature, and food availability, but their ability to enter cryptobiosis ensures survival under unfavorable conditions. They disperse easily via wind, water, and animals, ensuring colonization of isolated habitats. Studying tardigrade distribution helps students understand global biodiversity and the ecological impact of microscopic life.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Tardigrades feed on plant cells, algae, and small microorganisms. Some species use a sharp stylet to pierce cells and extract contents, while others scavenge detritus or prey on smaller organisms. Nutrient intake is critical for energy and cellular repair, especially during periods when cryptobiosis is required.

Observing feeding behavior offers insights into microscopic predator-prey interactions and energy acquisition strategies. Students can learn how diet influences survival under extreme conditions and how even tiny organisms play roles in broader ecosystem processes.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Tardigrades reproduce both sexually and asexually depending on species. Eggs are laid in moist environments and are often cryptobiotic, surviving harsh conditions similarly to adults. Juveniles resemble adults and undergo multiple molts before reaching maturity.

Reproductive strategies ensure population persistence under fluctuating conditions, and genetic diversity allows adaptation over generations. Observing reproduction under a microscope teaches students about developmental processes and microscopic ecology, providing lessons in evolution, resilience, and adaptation.

Space Survival and Astrobiology

Tardigrades are famous for surviving space conditions. Experiments aboard satellites exposed them to the vacuum, radiation, and extreme temperatures of outer space, with many surviving unharmed. These findings make tardigrades models for astrobiology and the search for life on other planets or moons.

Their survival mechanisms—DNA repair, protective proteins, and cryptobiosis—help researchers explore how life might endure extraterrestrial environments. Space experiments also inform strategies for human cellular protection in extreme conditions. Students studying tardigrades see direct connections between biology, space science, and molecular adaptation.

Importance in Research and Medicine

Tardigrades provide insights into cellular protection, DNA repair, and protein stability. Their stress tolerance informs research in medicine, including organ preservation, radioprotection, and therapies for degenerative diseases. Studying their cryptobiosis mechanisms helps develop biotechnologies for extending cell viability and resistance to damage.

Protective proteins and antioxidants from tardigrades inspire potential applications in medicine and biotechnology. Observing these tiny organisms allows students and scientists to see how studying extreme life forms contributes to real-world innovations, demonstrating the broader value of basic research.

Education and Citizen Science

Tardigrades are accessible for classroom study. Students can collect moss or lichen, extract tardigrades, and observe them under microscopes, learning about movement, feeding, and reproduction. This hands-on approach teaches microscopy, biology, and ecology.

Citizen science projects track tardigrade distribution and diversity. Participants collect samples and report findings, contributing to global research. Studying tardigrades engages students in scientific methodology, observation, and the principles of resilience, adaptation, and microscopic ecosystem dynamics.

Add comment